A mountain landscape near Madrid

Date

2023-2026

Location

Madrid (Spain)

Type

Residential

Trees

70

Area

5.000 m²

Status

Construction

This garden in the Sierra de Madrid has been conceived with sincerity and respect for the mountain. Inspired by the philosophy of John Ruskin, we have worked with local materials, always adapting to the environment. The design establishes a gradient of intervention: a setting close to the house with a stronger aesthetic presence, gradually transitioning into the natural landscape, where the garden merges with the sierra.

John Ruskin’s philosophy, which defended the truth of materials and sincerity in relation to nature, has been a point of reference in this project. Ruskin understood beauty as the result of working with what already exists, without disguises or unnecessary ornaments. From this perspective we wanted to approach the design of this mountain garden: not by imposing forms foreign to the place, but by seeking the beauty of what was already present on the slope.

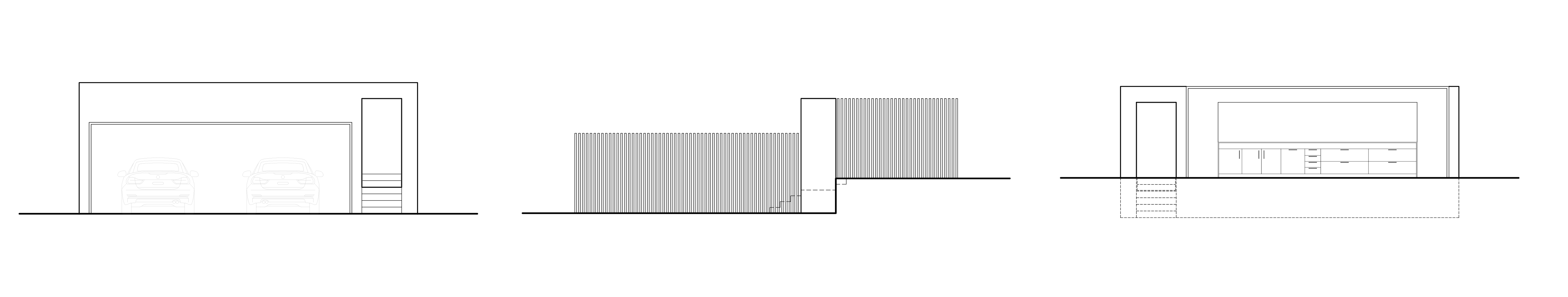

The house, conceived as an alpine architecture adapted to the terrain, is located on a slope with open views over the valley. This integration of the building on different levels allowed us to imagine a garden equally adapted to the contours. During the construction process, exhaustive monitoring was carried out of all the existing trees and species, ensuring that the machinery respected the vegetation as much as possible and that the topography was barely altered.

To retain the terrain and create different living areas we designed a system of wooden retaining structures, without using concrete or cement. The pieces are arranged in a fan shape, generating dynamism and visual movement, while at the same time allowing water to flow freely down the slope. In the plantings we followed the pattern of the mountain ecosystem: Cistus ladanifer, Quercus ilex, Juniperus communis, Retama sphaerocarpa, Thymus vulgaris and other local species that guarantee adaptation and coherence with the landscape.

Another fundamental aspect of the project is how the garden is conceived over time. In the immediate surroundings of the house, the entrances, the pool and the living areas, we designed spaces with a more ornamental character, where planting and maintenance have a greater aesthetic presence. However, as we move away from the house, the intensity of the intervention progressively decreases until it merges with the natural landscape of the Sierra. This gradient is intentional, part of the design: maintenance is adjusted to each area, from more regular care in the inhabited core to minimal attention in the more distant areas, where the ecosystem is allowed to evolve spontaneously.

In this way, the garden does not end at a clear boundary, but gradually dissolves into the mountain. It is not about controlling every corner of the plot, but about allowing new species to appear, animals to cross freely through the wilder areas, and the ecosystem itself to set its rhythm of evolution. The maintenance plan takes this logic into account: on the edges, weeds or spontaneous plants will not be eliminated but lightly managed, only as necessary to sustain the space over time. In this way, the garden becomes a living transition between the house and the landscape, a space that does not impose but accompanies, and that over the years will gain naturalness and character.

ABOUT JOHN RUSKIN

JJohn Ruskin (1819–1900) was one of the great thinkers of the 19th century, an art critic, writer, and social reformer. In works such as The Seven Lamps of Architecture or The Stones of Venice, he defended an idea that remains inspiring today: the truth of materials. For Ruskin, beauty does not arise from artifice or disguise, but from respect for the nature of each material, from the sincerity with which it is used, and from the honest relationship with the environment where it is built.

In our project in the Sierra de Madrid we wanted to bring this perspective. We worked with the materials of the place — granite in different grain sizes, wood arranged in a fan shape to follow the contours — and we avoided artificial solutions such as concrete retaining walls or plastics under the pavements. The goal was not to add unnecessary ornaments, but to discover the beauty of what was already present in the mountain, adapting the garden to the topography, respecting the existing trees, and maintaining the character of the place.

From the perspective of the landscape architect, we understand that to design is not to impose, but to dialogue with what nature offers. This search for a sincere beauty, without embellishments, is where we feel Ruskin’s legacy most alive when applied to the landscape.